So I sit down to write my first novel. It’s a big step. You have to convince yourself that you are worthy of the task and, more importantly, that you will complete it. There is no trying a novel on for size. You are either “all in” or you’re not.

I am all in. The research is done. I have a good starting point, the lead characters are developed and I know how the story ends. I am writing.

And it is going well. None of the blank screen issues are slowing me down; I’m piling up page after page, the first chapter is taking shape – until I get to the first sex scene – and then everything comes to a grinding halt.

It’s not that I hadn’t considered the question. Having been raised on the likes of Philip Roth, John Barth, Mary McCarthy and James Clavell, I always assumed there would be sex scenes in my book. I just had never written any.

I find there are a myriad of choices to make. How far do I let the characters go? Do I stop them at first base and fade to black? Second? Third? Is it necessary for the reader to watch them go all the way? How much detail is too much detail? How do I get them undressed without slowing the scene down?

I shrug off my hesitation, remind myself that I’m “all in” and dive into the scene. I’ll edit later.

At first, I’m enjoying it. And then I hit another snag. The word “penis” seems too clinical. Same with “vagina.” And even if they weren’t, how many times can you say “penis” and “vagina” without getting redundant or silly? I Google euphemisms and they all sound like the stuff of bodice rippers. His “burgeoning manhood” and her “nether lips” aren’t helping. The scene is getting worse. How do you describe pubic hair without saying “pubic hair” – especially in an historical time frame? I find myself avoiding the word “hard” no matter what the context. “Throbbing,” too, is out. I limp through the end of my tumescent scene and put it away, chastened by the undulating process, gorged with euphemisms.

A few months later, I take a summer refresher course at Dartmouth College on creative writing taught by author Barbara Dimmick (In the Presence of Horses, Heart-Side Up). We, of course, had to read our work in class for discussion. I read my chapter, sex scene and all and it became the focus of the entire hour.

“If you are writing to titillate the reader – or yourself – you are writing for the wrong reason,” Dimmick warns.* “There are no generic sex scenes. Sex is so intimate that it changes with each partner. Couples create their own language for sex; they go so far as to name the intimate parts of their bodies. They have their own signals for intimacy, their own rituals for foreplay. To be credible, the scene must reflect that level intimacy. It should give your readers insights into your characters, not you.”

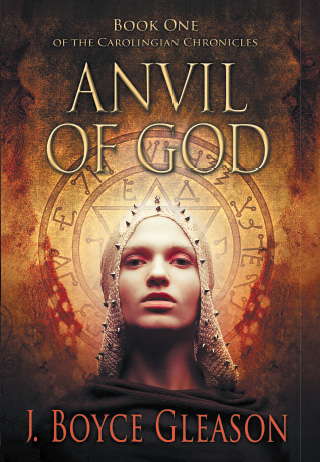

There are more than a few sex scenes in Anvil of God. But I make no apologies for them. They present a unique window into each character’s identity. It’s like pulling aside the curtain in the Wizard of Oz. We see them naked, (literally) without the clothing of their persona for the outside world. For Trudi, sex is an act of independence; for Carloman it is a counterpoint to the rigidity of his religious beliefs, for Pippin an expression of joy and respite from the violence of his life. The scenes advance the story in a way no other scene could.

I have found it more difficult to explain this to friends and people I know (for which such topics are usually off-limits). But then, as an author, I don’t have a choice. I have to be all in. Or I can’t be an author at all.

Next: What will the children think?

* Quotes are based on my admittedly limited memory and should be considered paraphrased at best.