So, there is a muse. I know, I know, it was news to me, too. I had always thought writers were referring to a person who inspired them not some mythical power that guides our hands as we put words on a page.

But she does exist. In hindsight I had seen glimpses of her influence throughout my life. A short story in high school that so surprised my English teacher that he read it aloud to the class, a term paper in college that seemed to write itself, an op/ed column I wrote under deadline when I wasn’t really sure what an op/ed column was. These moments persisted throughout my career but I shrugged them off as just good fortune.

As someone who avoided college courses if they required papers over ten pages long, I was surprised to find myself in jobs that demanded a substantial amount of writing, first as a press secretary, then as a newspaper columnist, and finally as a PR professional. I put in my ten thousand hours and knew I could compose a good sentence or two, but I would be lying if I thought it was anything close to inspired.

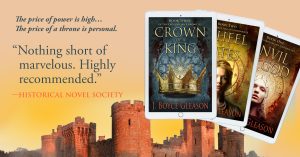

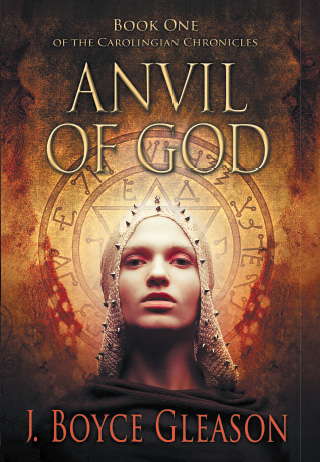

Curious to see if I could write fiction, I set aside one afternoon to try my hand at the story which would become the basis for “The Carolingian Chronicles.” I hadn’t done any research and didn’t have a plot. I just wanted to attempt creating a scene to set the stage between my protagonist (Charlemagne) and my antagonist Childeric (the last of the Merovingian kings). I made one good and one evil and began to write.

I stumbled along for a half hour or so trying to define a time and place. I put Charlemagne and his father outside hawking and Childeric inside the throne room. I introduced an envoy from the Church to Childeric and …

Three hours later I looked up. It was dark outside. I felt like I’d been drugged. I barely remembered writing the dozen pages before me. Worse, when I read the pages, I was shocked at how depraved they were. I couldn’t believe what I’d written. Embarrassed, I slammed down the cover to my computer and refused to look at the story again. I began to worry about my mental make-up and what such debauched thinking could mean about me.

It took me years before I unraveled what had happened. I had created an evil character and had let that character drive the story. It was almost as if I was along for the ride. At every turn, he took the tale to a very debased place. It’s what evil characters do when given half a chance.

I’ve since learned to set better guardrails for my characters so they no longer run amok with my storytelling. It helps that my characters are based on historical figures. I try to imbue them with attributes that explain the choices they made in history. Long before I put fingers on a keyboard, I spend hours envisioning them as real people with complicated life stories and nuanced world views. I never define a character as good or evil as I don’t know anyone who can be described that way.

But, once those parameters are established, the ride is still very much the same. The muse swoops in and words seem to appear on the page as if by magic. Hours fly by in moments. Dialogue sizzles in ways I don’t anticipate as the characters interact. The story takes unexpected leaps and turns that surprise me. It’s almost like I’m reading the novel myself rather than writing it.

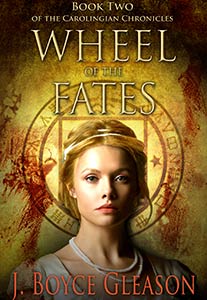

One recent example: To flesh out a character’s back story in Book II of the “Chronicles,” I created a religious sect devoted to “justice.” In writing the scene, the character referred to it as “the dark path.” I didn’t like the term as it felt Satanic, so, I changed it to the “iron path” in the next draft. I still wasn’t happy and went back and forth with it in editing. Finally, unable to decide, I left it where it started. Two years later, while finishing Book III, I discovered why it was called the dark path – it was an “aha” moment that resolved several themes I’d been working through and helped to pull the whole third novel together.

Not sure I can take credit for such foresight. It had to be the muse.