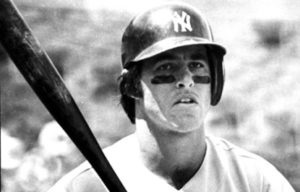

Say the name, “Bucky Dent” aloud in Boston and you will stop any conversation cold. No one ever says, “Bucky Dent” in Boston. They say, “Bucky Fucking Dent.”

Say the name, “Bucky Dent” aloud in Boston and you will stop any conversation cold. No one ever says, “Bucky Dent” in Boston. They say, “Bucky Fucking Dent.”

Some might think it odd that the name of a New York Yankee short stop would be so universally recognized in Beantown, but to almost any Bostonian Dent’s name symbolizes eighty-four years of anger and frustration at the Red Sox’s inability to win a World Series.

It was in Boston, October 2, 1978; the Red Sox were playing the Yankees in a tie-breaking playoff game for the American League East Championship. Dent, who was not known for his hitting, batted ninth and had very few homeruns to his name. Yet that night, Dent hit a three-run homer over the Green Monster to give the Yankees a 3-2 lead. They went on to win the game and afterwards the World Series. It was yet another close call with no reward in a city desperate for satisfaction. Worse it was a loss to their perennial rivals from New York.

In Boston, they hate New York. After that night, they hated Bucky Dent.

And, I was there.

Not at the baseball game – I was in town with my older brother Goose. Despite the fact that we are both from New York, we had come for the Harvard v. Dartmouth football game that Saturday and were staying at our fraternity’s headquarters on Bay State Road, commonly known as “The Grand Lodge.”

We had met up with a bunch of Dartmouth guys for the night and ended up in the wee hours at Kenmore Square, only about six blocks from the Grand Lodge. The place was packed with a sea of people, almost all of who were drunk and hungry for an early morning hoagie. There were maybe ten of us, striving to make our way through the crush of bodies to the counter. There were so many people, like Times Square on New Year’s Eve, you couldn’t move anywhere in a straight line. You had to move with the ebb and flow of the crowd’s tide to make your way.

I was about ten yards into the fray when I heard shouting behind me.

“New York sucks! New York SUCKS!” Clearly, the post play-off game fury had set in and some of the folks by the door were taking it personally.

I turned around just in time to see my brother sucker punched in the face by a guy with a buzz cut. Fists started flying and I realized Goose was grossly outnumbered. I looked for my Dartmouth friends to call for help, but they were too far away. I shouted, but they didn’t hear me and I knew if I tried to reach them it would be too late to help Goose.

I headed back. By the time I got to him, a cop had arrived. He was African American. There were about six or seven guys from Boston on one side of him and Goose on the other. I stood next to Goose.

“What’s going on here?” The cop demanded.

“That guy,” shouted Buzz Cut, “shit on Boston.”

“All I said was, “I’m from New York.” Goose wiped his nose to see if there was blood.

Someone in the crowd started taunting the cop, using the N-word.

“Are you going to let him shit on Boston?” Buzz Cut asked.

The cop looked worried. He, like Goose, was outnumbered and the crowd was turning ugly. Again, I heard the N-word.

“I want all of you out of here!” The cop waved his Billy club. “If you aren’t off this street corner in ten seconds, you’ll be arrested.”

I looked at the guys from Boston. They were itching for a fight.

“I’m out.” Goose walked away.

I knew they would follow.

“Wait. Goose! Let’s get arrested.”

“What? No. We’re done here. It’s over.”

“Please, Goose. Stay here. It won’t be so bad.”

I watched him walk away. The Boston guys were laughing. The cop was gone and Goose was heading back towards Bay State Road. I didn’t have a choice. I went with him.

“You know they’re coming.”

“Nah. It’s over.”

But, I could see them in the shadows behind us. I reached into my pocket. I had a lot of loose change. I shook the coins into my hand to give my fist weight and prayed I wouldn’t need it.

We walked the two blocks to Bay State Road and turned left. There was a streetlight on the corner and a party across the street in one of the row houses. People had spilled out of the front door into the yard.

They were still behind us. Four blocks to go. Three. I saw some movement across the street. It looked like a couple of them were running ahead of us.

“Hey, New York.” It was Buzz Cut.

“It’s over.” We kept walking.

“Hey, New York! Talk to me.” They were right behind us.

We turned. “Look –

Both Goose and I got hit from behind.

Now, I don’t know why I didn’t go down. The guy who tried to tackle me hit high and I instinctively bent at the waist. His momentum flipped him over me and he landed on the ground in front of me. I punched him in the face.

Goose had gone down, but I had other worries. I was surrounded.

Now, I’m not going to lie; I was scared. I felt my bowels start to give. (That’s right, I almost literally shit my pants). It was a “fight or flee moment” and it looked like I was going to fight.

They were taunting me. “Fuck you, New York.”

“We are going beat the shit out of you.”

I struggled to control my fear. There was a fence nearby and I figured if I could get my back to it, at least I would see the attacks coming. Unfortunately, one of them stood in my way. I hit him in the face and ran past him to the fence. I turned back – and realized my mistake. Now, I had nowhere to run. They stood in a semi-circle around me.

“How brave. Seven against one.”

Buzz Cut smiled. “That’s right. But, we’re going to kick the shit out of you.”

It was then I remembered the house party down the street. Maybe if I could fight my way there, someone would help. It wasn’t much of a plan, but it was a plan. I sized up the guys on that side of the semi-circle and picked the smallest one. I ran right at him and punched him in the face. To my surprise, he went right down and I sprinted past him.

They were on my heels. I got to the sidewalk and felt someone grab my shoulder. I turned. It was Buzz Cut. We threw a flurry of punches, none of which seemed to land, but it gave me some space. I back-pedaled. Another flurry and I ran to the corner. They followed, The streetlight was one block up. It was Buzz Cut doing all the fighting. He chased as I back-pedaled. We’d exchange blows and I’d keep moving. One more block to go. I got about halfway down the street when Buzz Cut picked up a garbage can and threw it at my head. I lifted a hand to block it and Buzz Cut tackled me. As I went down, the others descended on me and started kicking. I covered up my head and hoped someone from the party would see us.

They did.

“Hey! What the fuck?! What are you doing to that guy?”

After a few moments the kicking stopped and a hand pulled me up. It was Goose.

“You all right?”

“Yeah.” The guys from the party had Buzz Cut, both arms behind his back and none of his friends in sight. He was younger than I expected. And, it was clear he was scared, expecting me to hit him.

“Get the fuck out of here.”

They let him go and he disappeared into the night. I turned back to Goose.

“What happened to you?” He looked untouched.

“The guy who tackled me, hit me in the head. I think he broke his hand. When I got up, he ran away. I followed you down here.”

And that was it. Other than a cut on my cheek and some bruised ribs, I was okay. Our buddies caught up with us later. They wanted to chase down the Boston guys, but I knew they were long gone.

After that, I never had any sympathy for Boston’s losing streak. Although I have friends from Boston, I didn’t cheer for them in 2004 when they finally won the Series.

If asked where I stood on the rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees, I would pause and smile and then say I was with Bucky Dent…Bucky Fucking Dent.

That always ended the conversation.

My wife worked on Capitol Hill. Her boss, unfortunately, had just lost his reelection bid in a tough Republican primary, but since my wife had expressed a desire to be a stay-at-home mom, we took his loss as a sign and redid our budget using just my salary. We had enough – just enough – for us to make ends meet.

My wife worked on Capitol Hill. Her boss, unfortunately, had just lost his reelection bid in a tough Republican primary, but since my wife had expressed a desire to be a stay-at-home mom, we took his loss as a sign and redid our budget using just my salary. We had enough – just enough – for us to make ends meet.