Merging your company with another can be a nightmare. And I was living one.

Sure, on paper it made sense. After downsizing our office to put us back in the black, it was easier to reclaim our standing in the marketplace through acquisition than trusting a slow, incremental-growth strategy. But, a merger-gone-wrong had been what started our troubles in the beginning, so I had little enthusiasm for another. I advocated for going it alone.

But it wasn’t my company and there were few other jobs out in the marketplace, so I acquiesced to our New York patrons and chose to make it work. My office was folded into a new firm, which was to operate as a separate stand-alone company. Given that our newly acquired partners were on an earn-out, I would no longer be in charge.

It wasn’t the best of circumstances but I had lived through worse. I made only one stipulation; due to my experience with another small, independent company, I insisted that the folks in our office have the option to keep their retirement and health insurance with the parent company in New York. They agreed and with the stroke of pen, I had a new boss and worked for a new company. We packed up our desks, moved into their space and began the process of integrating our business.

To make a long story short, it didn’t work. We had different business models, different management styles and different approaches to the marketplace. And, as happens in these types of cases, the internal politics grew uglier as the situation deteriorated.

Unfortunately, I was the guy caught in the middle. The management of the new venture treated me as an outsider – potentially, even a spy for the parent company – while the folks in New York were suspicious of my up-front opposition and worried about my commitment to the project. It was a no-win situation.

It didn’t take me long to realize just how vulnerable I was. I was a convenient foil for everyone to blame as the merger struggled forward. It was like I had the word “scapegoat” stamped on my forehead. One misstep and I was out of a job.

And I could not afford to lose it. I had a wife, three kids, a dog and a mortgage. I had to work. In truth, I wanted the merger to succeed. It had to succeed.

Then I found out I had Rheumatoid Arthritis.

I had gone out for a run around the block with my oldest son to work off some of my extra weight. As a former athlete, I was shocked when I couldn’t keep up with him. I pushed it, trying to chase him down, but nothing I could do would close the gap. I came home stunned. My son was only ten years old.

Other problems surfaced. After my ninety-minute, morning commute into town, I had trouble getting out of my car and walking to the elevator. On a business trip, I couldn’t lift my suit bag out of the trunk of my car. I thought I had slipped a disk. That summer, I couldn’t push myself out of a beach chair. It was as if I had turned ninety over night.

For those who don’t know it, RA is a horrible, painful, autoimmune disease that slowly disfigures and cripples those it afflicts. RA sends the immune system into overdrive until it attacks and destroys the joints of the body itself. There is no cure.

I found a doctor who told me what was wrong and was given the standard treatment for the disease: a regular dose of methotrexate (a cancer drug) and an anti-inflammatory in an effort to slow the progress of the disease.

It didn’t work. My body ignored the benefits of most of the drugs they gave me (and we ran through a number). My doctor said I should contact a patient group and perhaps get some counseling. My body felt like it was rusting. My movements started to slow. I had trouble with simple things like turning a doorknob, climbing the stairs and even walking across a room.

I was thirty-eight, felt ninety and was scared out of my mind. How much longer would I be able to work? How would I pay for my kids’ education? How would I pay the mortgage, the medical bills, our day-to-day expenses?

But, for the moment, I couldn’t focus on the bigger questions. I had more immediate concerns. I had to keep this job. I knew what a pre-existing condition meant and was suddenly stuck with the knowledge I would always have one.

I chose to keep the illness a secret. I refused to tell anyone at work. I didn’t dare trust them. It would be too easy to isolate me – leave me out of new business meetings, or take away my direct reports – all in the name of being “compassionate about my suffering.”

It wasn’t being paranoid. It was being realistic. I couldn’t afford a gap in coverage. If I lost my job I would be uninsurable unless I found an employer large enough to wave the restriction – and one magnanimous enough ignore the implications of my disease.

I was stuck. So, I suffered in silence, steeled myself against the pain every time I shook someone’s hand or opened a heavy door. I made an art out of “sauntering” to disguise the slowness of my walk.

As to the merger, I had to find a way to de-escalate my vulnerability. There is an old business saying, “Keep your head down and let the elephants fight.” It became my mantra for the next two years. I took myself out of the role of middleman by suggesting that the folks in New York deal directly with our new partners. I kept away from the firm politics, kept my clients happy and kept the business coming in.

It took two years, but my luck finally turned. The five-year earn out was up and the folks in New York had come to see the merger for what it was. They jettisoned the acquisition of their own accord and asked me to retake the lead of the Washington office.

I had outlived the merger. And because I had kept my health insurance with the parent company, I did not have to reapply for coverage after the acquisition failed.

I was also fortunate that new medicines were discovered to treat and manage RA. Wonderful drugs like Enbrel and Humira gave me a new lease on life. I was like the Tin Man after Dorothy applied the oil. It was a miracle of modern medicine, albeit an expensive one as it cost an additional $1,500/month. But compared to a wheel chair it was not much of a choice at all.

I worked for the same company for twenty-five years. Now, there are several reasons for such loyalty. I was challenged often and made pretty steady progress up the corporate ladder (the above situation excepted). I liked the people I worked with and trusted their skills. But, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to being afraid of losing my insurance. As long as I was employed where I was employed, I’d be safe.

Many years after the merger, I left the company and struck out on my own with a couple of clients. I was able to skirt the pre-existing condition issue by keeping my company’s insurance through COBRA. And due to a change in the law under the Clinton Administration, I was able to keep my COBRA past its one-year limitation – as long as I agreed to pay both the company’s share of the bill and mine. It was incredibly expensive, but with a family still dependent on me, it was the only option I had.

After nearly a quarter century with a pre-existing condition hanging over my head, the issue became moot under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). I finally was able to purchase insurance in the open market. It was a huge relief – a stunning relief. Free at last!

When I let go of my COBRA-created insurance plan, I received a notice advising me that that once the plan ended, it was gone; I wouldn’t be able to get it back. But, I was confident that Congress wouldn’t take back a program they had extended to all Americans, especially, since it is so much like the benefit they receive under their federal employee health insurance.

Now, of course, I’m beginning to have some doubts. Will I be able to continue my coverage if Congress and the President repeal the ACA as promised? It hasn’t gone unnoticed that I have to “reapply” for my insurance every year in the open market.

They have vowed to replace ACA with a better plan. The question I have is, “Better for whom?” Believe me. It’s not a paranoid question; it’s a realistic one.

My wife worked on Capitol Hill. Her boss, unfortunately, had just lost his reelection bid in a tough Republican primary, but since my wife had expressed a desire to be a stay-at-home mom, we took his loss as a sign and redid our budget using just my salary. We had enough – just enough – for us to make ends meet.

My wife worked on Capitol Hill. Her boss, unfortunately, had just lost his reelection bid in a tough Republican primary, but since my wife had expressed a desire to be a stay-at-home mom, we took his loss as a sign and redid our budget using just my salary. We had enough – just enough – for us to make ends meet.

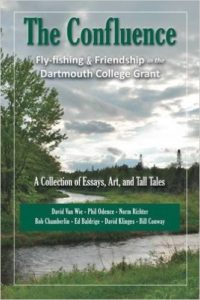

One weekend out of the year is reserved for these seven graduates from Dartmouth College, who fly fish in the pristine New Hampshire woods of the Dartmouth Grant. At times very funny, sad, and deadly serious, the book is a tribute to their secret identities as outdoorsman and renaissance men. It is a wonderful blend of tall stories, personal growth, poetry, music, some surprisingly good painting and their secrets of fly fishing brook trout.

One weekend out of the year is reserved for these seven graduates from Dartmouth College, who fly fish in the pristine New Hampshire woods of the Dartmouth Grant. At times very funny, sad, and deadly serious, the book is a tribute to their secret identities as outdoorsman and renaissance men. It is a wonderful blend of tall stories, personal growth, poetry, music, some surprisingly good painting and their secrets of fly fishing brook trout.