I grew up in a quiet little place called Briarcliff Manor. It was off the beaten track, a “village” dwarfed by three larger towns. Fewer than one hundred kids graduated high school with me and I’ll bet half were around twelve years earlier when I attended Miss Barnes first grade class.

Not much went on in Briarcliff and our parents liked it that way. We had a police force, but not much in the way of crime. We had a “main street,” but it had stores on only on one side of it. For the most part, during my formative years, days were filled with playing football, basketball or baseball (depending on the season), hanging out, reading comics, riding my bike and trying to figure out how to talk to girls.

Our high school stood in the center of town next to the community pool, the park and the library. It had a large green lawn, a flagpole and a circular driveway out front for the buses to come and go. It looked like a Spanish fort, with high stucco walls and an imposing facade. Everyone called it “The Alamo.” The Rec Center used to sho

w movies against its front wall during hot

summer nights and families would turn out, sit on blankets to watch, “The Mouse that Roared” and “War of the Worlds.

Oddly enough, The Alamo was an

appropriate name for 1970, when this story takes place, as most of our

parents were desperately trying to keep the outside world from invading the quiet life of our little village. Six years after the

Beatles had landed at JFK, the country had transformed itself into something unrecognizable to them.

Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, The Doors, Meatloaf were merely symbols of the type of change rocking the country. The Kennedy brothers had been assassinated; so had Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. People were marching in the streets for civil rights, women’s rights and against the Vietnam War. With the invention of the pill, the sexual revolution was in full swing and our parents were more than a little worried.

You could see the change in school. Boys started wearing their hair long; everyone sported jeans and tie-dyed tee shirts. Drugs found their way into student lockers and everyone was talking about the Vietnam War. Congress had done away with the college deferment and instituted a lottery system for the draft. All 18-year old males, including those in that year’s senior class, were eligible.

Although, I loved the music, I was largely unaffected by the changes going on. The son of a Marine, my hair was still short and my politics, if you could call them that, were conservative. At the time, I was thinking of going to West Point. I found the changes that many of my friends were going through perplexing. I hung back, preferring the company of my football buddies, and kept my nose clean.

Critical to this story is Kevin Johnson, a junior at the time. Kevin scared the crap out of me. There was a nervous edge about him – an “I don’t give a shit” edge – that a straight-laced fourteen-year-old boy like me found incomprehensible. Making matters worse, he didn’t like me. If he walked into a room, I’d check for the location of all the nearest exits before I took my next breath.

It was in early May when our moment of truth arrived – a breach in The Alamo. It began with an announcement by President Nixon that the U.S. would bomb Cambodia (to stop the North Vietnamese from using that country to make end-run attacks on our troops). College campuses all across the country were in an uproar of protest, with sit-ins, marches and candlelight vigils.

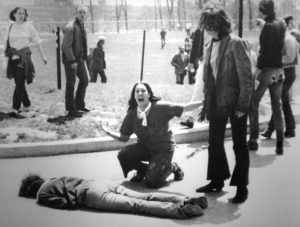

One such protest was held at Kent State University. Although it started out peacefully, unruly behavior among the protestors and some poor decisions by the mayor of Kent caused the situation to escalate into violence. The mayor called on the governor to issue a state of emergency. The governor concurred and called in the National Guard.

A second day of protests started and the confrontation continued to mount. Someone set fire to the ROTC building and a thousand protestors surrounded the blaze to cheer. When police and fire fighters arrived at the scene, they were pelted with rocks. In the ensuing exchange a student was bayoneted. The governor called the protestors “un-American” and vowed to “eradicate the problem.”

Cooler heads among the students tried to prevail. Several showed up the next morning to clean up the mess from the riot but were ordered off the streets. The protestors tried a new tack, holding a sit-in in hopes of securing a meeting with the mayor and the university president. The National Guard used tear gas and fixed bayonets to disperse them and several more students were stabbed.

A fourth day of protest started and the Guard was ordered to clear the campus commons. After tear gas canisters were ineffective, the Guard again fixed bayonets and marched on the protesters. They succeeded in dispersing a majority of the students, but some remained on the steps of a nearby campus building. They heckled the Guardsman marching back through campus. One of the Guardsmen, a sergeant, turned and fired into the protestors. Twenty-nine members of his platoon turned and fired as well. In all 67 rounds were fired, killing four students and wounding nine others. Two of those who died were protesters; two – including one young man who had been in the ROTC – were simply on their way to class.

Their deaths rocked the country. Back in Briarcliff, Doc. Pruitt suspended his lesson plan and opened our 9th grade history class to discussion. I was stunned by the vitriol of the opinions on both sides and I couldn’t believe anyone could see it differently than I did.

Their deaths rocked the country. Back in Briarcliff, Doc. Pruitt suspended his lesson plan and opened our 9th grade history class to discussion. I was stunned by the vitriol of the opinions on both sides and I couldn’t believe anyone could see it differently than I did.

“Who started the violence?” I demanded. “Who torched the ROTC building?” The debate became heated and at one point I shouted a slogan used often back in the day. “If you don’t like our country, why don’t you leave it?”

After class the argument spilled out into the hallway. Everyone was angry. Kevin came around the corner with a look of exuberance on his face. “Someone lowered the flag to half-mast. It’s for the four students!”

“Well that’s not going to happen,” I said, and, without thinking, stormed off to the front lawn. Kevin followed, stalking my steps.

“What you going to do?” Menace poured from him.

“Raise it back up.” I kept my eyes ahead, afraid to look at him.

“Why?”

“It’s just not right.”

We went back and forth all the way to the flagpole. Kevin was so mad he was spitting. I untied the cord securing the flags but he grabbed it above my hands to stop me. Here it comes, I remember thinking. He’s going to beat the shit out of me. But, I wasn’t backing down.

“What’s going on here?” Bob Prout, the dean of students, seemed to appear out of nowhere. And he wasn’t alone. My older brother Jim, Michael O’Hagan and Deryl Seemayer (three of the biggest guys on the football team) all stood behind him. My confidence was magically restored.

“Someone lowered the flag to half-mast. I came to raise it.”

“Go ahead.” Dean Prout folded his arms.

With a look of betrayal and fury Kevin flipped us the bird. “This is all bullshit!”

He stormed away as I pulled on the rope to lift the flag. I felt vindicated in my actions. I felt proud to have faced down my fear. And, I felt relieved that Kevin didn’t beat the shit out of me.

But, looking back on that moment, I see the world a little differently. Kevin was right. And I’m ashamed to say that it would not be the last time that I found myself on the wrong side of history.

Although there was plenty of blame to go around in the tragedy at Kent State, just as there is in the state of our politic today, I got caught up in the rhetoric. I lost my perspective. It was a shameful day and a lesson in what happens when antagonists double down on their righteousness. Those students didn’t deserve to die and their death was a national tragedy. They deserved to have our flags lowered on their behalf. To function, democracy requires a unique talent – the ability to listen – especially by those in power, and especially if they carry guns.

No one was listening that day in Ohio on either side and we all paid the price for it, especially those four kids. They deserve our apology and, for my behavior that day, so does Kevin Johnson.

You were right, Kevin. It was all bullshit. And I’m sorry I wasn’t smart enough to see it. Maybe next time I will

Meā culpā, meā culpā, meā máximā culpā.