It started as a day laborer job. The folks who were the caretakers of “The Alamo” (our ancient high school building) were regularly trying to keep the place from falling down and needed a couple of young guys to carry fifty-pound cement bags and cinderblocks up three flights of stairs.

Football players proved to be just the ticket they needed. My brother John (who had the job before me) greased the skids with the janitor corps and before I knew it my buddy Pags and I were employed. And in those knuckleheaded days of our youth, we loved hauling cinderblocks. We carried two at a time, racing up the stairs to prove our worth. It was good, exhausting work; we were happy for the money; and we enjoyed the grown up banter of the workmen.

They were a jovial group with a somewhat jaded view of life and a penchant for dirty jokes. The top guy for the whole school district was Richard Collachio (I’m sure I’m spelling his name wrong). He was a red-haired Italian American who was always in such a hurry that he was perpetually out of breath and covered in sweat.

No one could move fast enough for Richard; he was always pushing our deadlines. But for all his hyper expectations, he always protected his “guys” (us) from the “folks upstairs” (the administration). And since most of the janitors hated dealing with the people who wore suits, they were happy for him to shoulder the burden.

Our immediate boss, Joe Bednar, was Richard’s polar opposite. Joe worked hard, but was done rushing around to impress anyone. He liked to enjoy life and was kind enough to bring doughnuts to our coffee break most days. And if we were having a slow one, sometimes he’d let those fifteen minutes slide into twenty, especially if we were having a good time.

He and Richard had a love/hate relationship. Richard was always pushing Joe to work harder, always sweating the details and Joe was as calm a cucumber as God could make. As cuss words go, their discussions were really impressive, but I always had the sense that they liked each other and much of what went on was for show. Joe always delivered the work on time, never said a cross word to us (save one time – but that’s a different story), and still found a way to smell the roses that crossed his path.

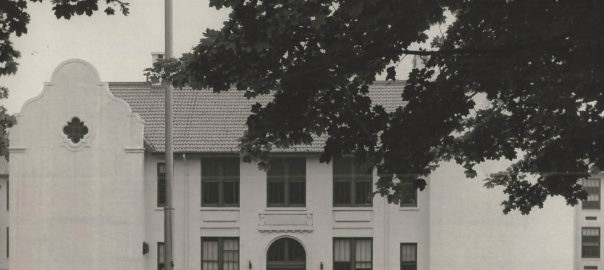

Our high school was an old behemoth of a building built in a by-gone era when people made things as a testament to their labor.

Our high school was an old behemoth of a building, built in a by-gone era when people made things as a testament to their labor. Originally built in 1911, it was enlarged with a second building (united by a corridor between them) in 1928. It had Spanish style architecture, (hence the Alamo moniker), huge windows and a nice-sized auditorium.

To keep the place in shape for the six hundred or so students or who occupied it, (from grades seven through twelve) Pags and I were employed to work summers, holidays, and through every spring break. Most of the time, we spackled and painted our days away, as there was always something to spackle and paint. (Think of those hundreds of little gymnasium windows that every gym has. Guess who had to re-caulk and paint those insidious monsters? Yeah that was an entire summer).

But, we also were regularly tasked with janitorial duties: mopping the floors, oiling down the gymnasium floors, cleaning the bathrooms, incinerating the trash, (ah, the good old days), scraping gum off the underside of chairs and desks (my least favorite job) and washing the windows.

The bathrooms, too, were always challenging. The graffiti in the boys’ and girls’ bathrooms (yes, we had to clean both of them) always shocked me. The graphic nature of the caricatures, the commentary and – yes – the medium was almost always beyond my belief system.

It made me question the sanity (and the sexual predilections) of many of my classmates.

Some were funny (at least to the juvenile me). “Here I sit broken hearted, have to shit, but only farted.” Most, however, were just gross. It made me question the sanity (and the sexual predilections) of many of my classmates. People used everything: pen and ink, used tampons, and soiled toilet paper to perfect their art. And Pags and I had to clean it all up, sometimes painting the stalls over three and four times (those indelible ink markers showed through everything).

We kept those jobs all the way through high school and got to know all the ins and outs of the place. I knew, for example, just how to kick the boy’s locker room door from the outside to yank it open without a key. On our breaks, we hung out in the teachers lounge, explored the hidden passageways between buildings, and got to know all the janitors and administrative staff on a first-name basis.

Mid-way through my sophomore year, the school district opened a new high school. Sam Brown became head janitor of the high school. He was a quiet soft-spoken man with a pencil thin mustache. Joe stayed at the Alamo (which had become the middle school), so Pags and I stayed with him. Over time, we took great ownership in the place.

Every fall, when the teachers arrived a week ahead of classes, I’d get a kick out of their reactions to the newly restored building. I remember the surprised look on their faces when we took off the walls of the library to give it, what today is called, an “open concept.”

As students, most kids start off resenting school. They are forced to get up early, take classes, in which, they have little choice, respond to bells like they are prison inmates, and are assigned homework that takes up whatever time is left in their day. The lucky ones find a coach, a teacher, or two who can inspire them, make them think, or awaken an unknown talent or interest. But rarely do students think about the administrative staff that also makes their education possible. It’s like they are on the other side of the looking glass. We know they are there, but that’s about it.

Pags and I had the rare opportunity to see the school from both sides of the glass.

Pags and I had the rare opportunity to see the school from both sides of the glass. We saw the effort required to keep an old building functioning while hundreds of students daily pushed it to its limits. We got to know the staff as good, kind-hearted people who earned their living each and every day. We saw the pride they took in keeping the place clean and the disdain they felt for the purposeful destruction of the property.

During the school year, Pags and I inevitably returned to the other side of the glass as students. The admin staff left us alone with our classmates. We were, once again, no longer part of their community, but of a community they served. Sure, they would smile or wink when we passed them in the hallway but it wasn’t the same.

Kids can be rebellious during their adolescence and I did a lot of things for which I am not proud (again, another story). But, for all the things I would do, I never left a mess in the cafeteria or trash on the school lawn. I never stuck gum to the underside of a desk or wrote graffiti on the bathroom walls – not because I might have to clean it up – but out of respect for those I knew who would.

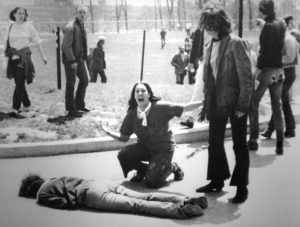

Their deaths rocked the country. Back in Briarcliff, Doc. Pruitt suspended his lesson plan and opened our 9th grade history class to discussion. I was stunned by the vitriol of the opinions on both sides and I couldn’t believe anyone could see it differently than I did.

Their deaths rocked the country. Back in Briarcliff, Doc. Pruitt suspended his lesson plan and opened our 9th grade history class to discussion. I was stunned by the vitriol of the opinions on both sides and I couldn’t believe anyone could see it differently than I did.

Much to my consternation, I attended high school during the one brief moment in time when being on the football team did not enhance one’s social status.

Much to my consternation, I attended high school during the one brief moment in time when being on the football team did not enhance one’s social status.