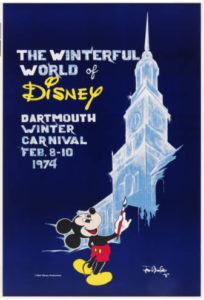

During my freshman year at Dartmouth, I had a Winter Carnival date with Kim Carr. To this date, when I say that, no one believes me. That’s because Kim was a brilliant young woman with a beautiful smile – and way above my dating pay grade.

To be honest, it wasn’t an official date. I had tickets to the Winter Carnival musical (I think it was Where’s Charlie) and when my on-and-off-again girlfriend from home couldn’t make it, I offered the tickets to Kim and her boyfriend Eric.

To be honest, it wasn’t an official date. I had tickets to the Winter Carnival musical (I think it was Where’s Charlie) and when my on-and-off-again girlfriend from home couldn’t make it, I offered the tickets to Kim and her boyfriend Eric.

“Eric isn’t coming to Carnival. But, I’ll go with you.”

Time seemed to slow down a bit then. I don’t remember exactly what I said in return, but I’m sure it was something witty like, “Okay.” (At that point in my life I hadn’t had a whole lot of dating experience and the experiences I did have, did little to build up my confidence).

I was nothing short of euphoric. It was like winning the Winter Carnival lottery. (There is no such thing, but if there were, it would have been like winning it). And although in the back of my mind I knew it wasn’t really a date, I thought maybe it could be. Maybe we’d hit it off. Maybe it would lead to another date. Maybe…

It was cold that year, made all the more so by the fact that the country was going through an energy crisis. The president had rolled back all the highway speeding limits to 55 mph and the school had voluntarily done its part by shortening the winter term from ten weeks to eight and dialing back the thermostats on campus buildings to a body-numbing 55 degrees.

The date was for Friday night of Carnival but on Tuesday I noticed a little soreness in my throat. By Wednesday it had gotten worse and brought a fever with it. By Thursday it was a real problem. I kept thinking, “Get through the date and then deal with it.”

Thursday night, I was in bad shape. My temperature spiked; I sweat through the sheets on my bed and several doses of aspirin did little to stop the onslaught. Determined to make my date, I stumbled my way to Thayer Hall Friday morning and tried to eat breakfast. I couldn’t even swallow.

I knew I had to go to Dick’s House. Dick’s House was the college infirmary, located just off campus and – at the time – next to Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital. Weak, bleary-eyed, and light-headed, I left my tray on the table and headed outside. Immediately the cold air froze the sweat on my body. As I stumbled my way down the street, I realized I was in trouble. Although Dick’s House was less than a mile away, I wasn’t sure I could make it.

“You look like, shit, Joey.” I don’t know who said that, but I was sure it was true.

“Dick’s House,” I mumbled and kept walking.

It was tortuous. I reached Sanford House. I made it to the corner of the Kiewit Center and threw up. I looked in all directions, praying for a friendly face or a campus police car. There was nobody. I was so cold.

I put one foot forward. Then another. And, after an eternity, I made it to Dick’s House. I stumbled up the steps and sat down to wait my turn, trying hard not to pass out in the waiting room.

“Joe?” It was Mary, the attending nurse. She was a friendly soul who liked to chat up her patients. “Bad timing to be here!” She led me back to the examination room and popped a thermometer under by tongue. “You don’t want to miss all the fun.”

She took out the thermometer and frowned. “Must not have shaken it out.” With a few snaps of the wrist she tried again. She put her left palm onto my forehead. “You’ve got a temp.”

This time, when she pulled out the thermometer, her eyes widened and her face grew pale. She leaned out the door and yelled. “DOCTOR!”

In seconds I strapped to a gurney with ice packs placed on top of me.

I woke up on the second floor of Dick’s House. It looked much like the large dormitory in Cider House Rules. (Good night you princes of Maine, you kings of New England). There were ten beds on each side of the room with little standing curtains to give patients a pretense of privacy. I was the only student there.

The doctor told me I had a severe case of strep throat and that my temperature had spiked to over 105 degrees. “You’re lucky we caught it there. At 106 degrees you start to die.”

A couple visitors came by during the day. I don’t know how they knew where I was. Kim showed up. I apologized for ruining the evening. I remember the Doctor asked her if she was the reason I had waited so long to come in.

On Saturday night I was alone. It was my first Winter Carnival and I was spending it in an infirmary feeling sorry for myself.

Until I heard a tap on the window. At first, I ignored it, but it came again. I climbed out of bed and went to the fire escape window and there were two of my buddies from the freshman football team: Rick Angulo and Wayne Watanuki.

“What are you guys doing here?” I whispered.

“We heard you were all alone so we thought we’d come by and cheer you up.” Rick pushed past me into the room. Wayne was right behind him.

They sat on the bed, beer in hand and we chatted about all the parties they had been to and how many girls were on campus. They heard a noise in the hallway and both of them hid behind the aforementioned curtains.

A nurse poked her head into the room and looked around. Seeing that I was awake, she said, “Can I get you anything?”

“No, thank you.”

After she left, they came out of hiding and we laughed quiet laughs. We talked for a few more minutes and then they stood up. “We gotta go,” Wayne said. “It is, after all, Carnival.”

“Thanks guys.”

As they left by the fire escape, Rick leaned over and pressed one of the call buttons. A light came on in the hallway. And then, Rick blew me a kiss, and they disappeared into the night.

After a minute the nurse came back in.

“Did you need something?”

“No.” (That, right there, was my big mistake).

“You didn’t turn on the light?”

“No.”

She frowned and went back down the hall. A little while later I fell asleep.

I woke up with the beam of a flashlight in my face. It was a Hanover policeman with two of the night nurses behind him. To say that he was angry is an understatement. He was furious and within an inch of my face.

“If you know something about what’s going on, you better own up to it. We’ve got patients here, elderly patients down the hall from the hospital who are frightened out of their minds. Someone’s been in here stealing drugs. If you know anything about that, now would be a good time to tell me.”

“What?” I sat up. “Stop. No one is stealing drugs. I’ll tell you what happened. A couple of my friends came up the fire escape to see me. I let them in. They didn’t take anything. All they did was turn on that call button on their way out.”

“What are their names?”

“I told you, they didn’t do anything.”

“If you could see the elderly patients down the hall, you wouldn’t say that.”

“I don’t know who frightened those patients, but it wasn’t us.”

“I want their names.”

I shook my head.

“You think this is funny? You are going to be held accountable for this. I’m going to file a report and submit it to your dean. I doubt you’ll be attending this school much longer.” He and the nurses stormed out of the room. I didn’t dare touch the call button again.

They released me on Sunday, just in time to hear about how much fun everyone else had over the weekend.

On Monday, I went back to class. I was taking Calculus 101. Unfortunately, I was hopelessly lost. I couldn’t even understand what Professor Slesnick was saying. I had struggled before my bout with strep, but now, with all the missed classes and the shortened term, I knew I would be hard-pressed to catch up. I needed a tutor and the only way to get one was to visit the dean’s office.

That was my next stop. At the time, Ralph Manuel was the freshman dean. I had met him several times on campus and he seemed like a good guy. Unfortunately, his office was packed. Fortunately, I only had to wait a minute. I stepped into his office and he waved me to a seat in front of his desk. He wasn’t smiling.

“I’m told that I need to talk to you about getting a tutor.”

His eyebrows shot up. “A tutor? Young man, you don’t need a tutor. You need a lawyer.” He handed me the police report from Saturday night. It made us sound like we were cavorting through the hospital and wheeling panicked senior citizens down the halls against their will.

“None of this is true.” And it wasn’t. It was way beyond embellishment.

“Well, I’m putting this before the College Committee on Standards and Conduct and I expect they will sever you from the school.”

“But, it isn’t true.”

“You can tell that to the committee. They meet on Friday.”

I was furious and panic stricken all at the same time. Thrown out of college? Getting into Dartmouth was the only major goal I had ever had. This was a mistake. And I said so.

“There’s only one thing you can do to avoid it. You give me the names of the two boys who came in through the fire escape and I’ll recommend to the CCSC that you get a reprimand.”

“And my friends will get kicked out.”

“Yes. It’s either you or them.”

I left. I had two brothers on campus. They offered conflicting advice. One said, “Give up the names. It’s your whole future at stake.”

The other said, “Fuck them. They can’t just throw you out without cause. If they do, sue ‘em. They can’t prove anything.”

I went to my two buddies. Both Rick and Wayne stood up to turn themselves in, but I held up my hand. “There’s no guarantee that the committee will grant me the reprimand. I may get kicked out anyway. This way only one of us goes. If you turn yourselves in, it might be all three of us.”

I didn’t tell my folks. I couldn’t come up with a way to start the conversation. But as much as I was panicked about the situation, I was angry. I was angry that the truth had been so twisted, so the nurses could save face. I was angry that no one even listened to my side of the story. And I was furious that I was being asked to turn in friends – who’s only crime was taking pity on me for being left out of Winter Carnival.

Friday came and I was ushered before the CCSC. The room was set up to intimidate. Two long tables had been arranged in the shape of a “T” with representatives of the faculty, the administration and the student body sitting around it. I sat facing them at the base of the T.

They read the police report aloud. One by one, the faculty raged against “drunken behavior” and “vandalism” on campus. They condemned the flaunting of authority and the recklessness of our actions. The students on the committee were less judgmental and wanted to know more facts about the case. None of the administrators spoke until Dean Manuel repeated his demand that I give up the names of my “co-conspirators.”

“I won’t do that.”

Silence took the room. One of the faculty members spoke. “You realize that if you don’t give us those names that we will hold you accountable?”

I nodded. Every face that looked back at me was grim.

“Do you have anything to say to the committee?” the faculty member asked. It sounded like a death sentence.

“Yes. I do. If this police report were true, I would agree with you that we should be thrown out of the college. Having fun at the expense of hospital patients is unconscionable. But that isn’t what happened. Yes, I let two of my friends in through the window at Dick’s house to visit me on Saturday night. They felt sorry for me because I was missing out on Carnival. All we did was talk. They didn’t take anything. They didn’t break anything. And they left. We never saw any other patients from the hospital and never spoke above a whisper. The nurses weren’t there. The policeman wasn’t there. I don’t know why they upset the patients down the hall.

“All I did was open a window. If that is enough for you to throw me out of college, then there is nothing more to say.”

They deliberated for an hour and then let me off with a reprimand. I sent a letter of apology to the head of Dick’s House for inadvertently setting off a scare. I never divulged the names of my two “co-conspirators” although Ralph Manuel for years has pestered me about who they are.

I also never had a date with Kim Carr. That moment, apparently, had passed, never to come again.

I also never had a date with Kim Carr. That moment, apparently, had passed, never to come again.

About ten years after we graduated, my buddy, Rick Angulo died of leukemia. It was hard to think of someone that full of life taken so young. For a time, he had been our president and it hit our class particularly hard. In a gesture of our grief, we donated the funds to plant a tree in his name on campus, so he’d always have a place of his own there.

When I got the notice about the tree, however, I started to laugh. And in my heart I knew that Rick was laughing too. It wasn’t about the type of tree they chose. It was about where they decided to plant it.

It stands, to this day, on the lawn of Dick’s House.

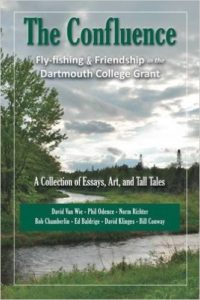

One weekend out of the year is reserved for these seven graduates from Dartmouth College, who fly fish in the pristine New Hampshire woods of the Dartmouth Grant. At times very funny, sad, and deadly serious, the book is a tribute to their secret identities as outdoorsman and renaissance men. It is a wonderful blend of tall stories, personal growth, poetry, music, some surprisingly good painting and their secrets of fly fishing brook trout.

One weekend out of the year is reserved for these seven graduates from Dartmouth College, who fly fish in the pristine New Hampshire woods of the Dartmouth Grant. At times very funny, sad, and deadly serious, the book is a tribute to their secret identities as outdoorsman and renaissance men. It is a wonderful blend of tall stories, personal growth, poetry, music, some surprisingly good painting and their secrets of fly fishing brook trout.